|

| Serlby Close, Usworth. The houses on the left are part of Coach Road Estate Source: © Alex McGregor at Geograph CC-BY-SA-2.0 |

I checked a few of these examples using available Open Data sources, primarily those of the Ordnance Survey. For the most part, our existing mapping seems correct: there is no official street name. Many were places like caravan parks and industrial estates, but one really stood out. This was an area on the north side of Washington, County Durham called Coach Road Estate. As I investigated it soon became apparent that the estate is interesting for other reasons too.

It's very unusual for roads in an urban setting to lack names. Although it is not uncommon in the countryside where addresses will be of the form <housename>,<village-name>. However it was very easy to verify that this was indeed the case for the Coach Road Estate. The main reason being the existence of an abundance of government open data about the site (nearly 700 records in all):

- Food Hygiene: a single convenience store is present.

- Naptan: bus stops on the estate all use the name, and conveniently often include the nearest house number.

- National Register of Social Housing. Although this stopped being maintained in 2011 it is still invaluable not just for addresses, but also to identify planned estates of social housing (council estates, colliery villages etc). There are hundreds of addresses ranging from 1 to 589 in this dataset (there are 648 records in total, but this includes a lot of garages). As they have postcodes they can also be geolocated.

- Companies House: five companies are registered at four addresses on the estate.

|

| Screenshot from Will Philips OSM-Nottingham website showing geolocated OpenData with "Coach Road Estate" in the address, name or other field. Unfortunately, I failed to screenshot this before mapping the area in detail. (Although the site is focused on the Nottingham area it now allows searches on most UK open data useful to OSM). |

It was also possible to add a few addresses from Naptan. This is a classic case where the addr:place tag can be used in addresses. Fortunately there were two bus stops close together on the NE corner of the estate which allowed, with some judicious guesswork, many more addresses to be inferred.

By now I had multiple other questions: When was the estate built? What types of houses? Was it planned as part of the New Town, or earlier? Was it constructed to provide housing for colliery workers? Can we find out anything about the layout?

Fortunately the first question was easy to resolve: the estate is not shown on maps from the 1940s and early 1950s, but is partially complete on those dated around 1960. This in turn suggests that it pre-dates the New Town, which was formally designated in 1964.

Washington, unlike other new towns, was not built on a predominantly green-field site. Rather it was already an area of piecemeal scattered housing and associated industrial areas (mainly collieries).

Dispersed settlement patterns of this type were quite common on British coalfields (the area where my father comes from Hollinwood, Oldham is an example from elsewhere, although the pattern has been obscured by later development). The development sits in the former parish of Usworth, which at the start of the 20th century contained a nucleated village, Great Usworth, a development of long terraces of workers housing extending piecemeal westward from Usworth Colliery, and scattered terraces elsewhere. These terraces would have provided very small basic houses, mainly for colliers. My great-grandfather, born around 1860, lived in such a house in Hollinwood. It was not a "Parlour House", but the main living area was entered directly from the street, behind this was a scullery with a slop stone (a large sink), and perhaps 2 bedrooms upstairs. The toilet was in the back yard. My father remembers that the front door of my great-grandfather's house was rarely closed, and a large coal fire was kept burning on even the warmest days (as a miner his coal allowance was more than they needed). Amazingly one of these terraces still survives in Usworth, Pensher View. Estate agent details suggest that this survival is because the houses were larger than typical, and capable of being updated.

|

| Prefabs in Sulvgrave Village (presumably those at Usworth Green). The terrace behind is probably Pensher View Photo from Tyne & Wear Archives and Museums via Flickr. Crown Copyright. More details on their Flickr page. |

For many fantastic photos, and other documentary evidence (including annotated maps), of this housing, the Raggy Speik website has been an invaluable resource. There is also a fascinating article about the local bus operator with great local colour on the Washington History Society website.

It was on this palimpsest of earlier developments that Washington New Town came into being.

|

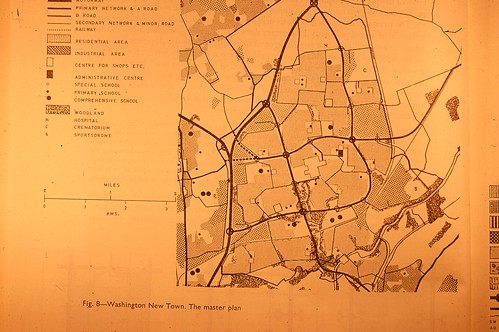

| Masterplan of Washington New Town from JR James Archive on Flickr (CC-BY-NA-2.0). Coach Road Estate is in the northernmost block of residential landuse zoning. |

The immediate antecedents of the New Town designation lay in the Hailsham report of 1963 ( written by Quentin Hogg, Viscount Hailsham). The North-East suffered from a number of problems: a ageing and, often out-moded, housing stock with over half from before WWI; the demise, or anticipated demise, of traditional sources of employment (mining, shipbuilding); poor communications, and much land in need of remediation. Unemployment, and housing shortages were leading to outward migration from the area, which meant that Hailsham's report was something of an emergency rescue measure. (See this thesis for more detail).

The existing new towns in County Durham, Peterlee and Newton Aycliffe, needed strengthening, and finally central government was now receptive to the demand from local authorities to grant the area around Washington the same status. Previous resistance had come from several sources: Sunderland Council, central planners who wanted greenfield sites, and ones which were self-contained for employment. However, it seems that at a local level the area had already been chosen for development, at least of housing: Concord, and, I suspect Coach Road Estate, are testament to that. The predecessor of the New Town, Washington Urban District was formed in 1922 and grew by absorbing adjacent areas.

The actual development of the New Town is beyond the scope of this post, but there are some nice images on John Grindrod's site from the master plan (including the fantasy by one of the artists of a Waitrose supermarket in the North East from the 1960s). Here I'll just note that the development area was divided into about 17 numbered communitie.s They later acquired formal names, and the area around Usworth Colliery became Sulgrave (named after George Washington's other ancestral village in Northamptonshire).

Coach Road Estate was earmarked for one of the local centres. This is the area next to St Bede's Catholic church, and incorporates a small number of shops, and a (former) pub, the Coach and Horses.

|

| Coach & Horses, Usworth in 2010 (now closed) Source: © Alex McGregor at Geograph CC-BY-SA-2.0 |

Of rather more use is the (probably) unusual layout of the estate. Firstly, it clearly incorporates provision for car ownership: something even early-post WWII estates did not do. Groups of houses face a service road at the rear giving access to garages and parking areas. The service roads do not appear to have pavements, but there may be very narrow ones. Virtually all houses front onto green spaces, either generous verges on the access roads, or, in the main, onto to the grass extents which separate clusters of houses. The primary access to the estate is via a loop road with just two access points to the main distributor road system. Pedestrians have an extensive path network in the estate and many more ways to leave it.

The obvious arrangements to both provide for, and separate out, the motor car, are strongly redolent of the Radburn approach. However, instead of motor access being via an external loop road with service roads penetrating into a doughnut of housing surrounding a green core, here the loop road is within the estate, and housing and green space are inter-digitated. For want of a better term I've called this 'Inside-out Radburn'. Ian Waites is currently researching Radburn designs, so I hope this might pique his interest.

This post has entirely been based on my delving into the likely circumstances which led to one small estate of houses having road name.

I think it demonstrates just one of the reasons why the history of such places is so fantastically rich. Indeed, when I read John Boughton's new book Municipal Dreams this summer, I was struck that the history of housing in Britain in the 20th century is pretty much the history of social housing. Compared with privately developed housing, there was more innovation (not always successful) more design, more depth of planning, and a greater commitment from architects, planners, engineers, and, a surprising variety, of industries. John's achievement in condensing this richness into 300 pages leaves me in awe, especially, as his own research as detailed on his blog is very much rooted in the intimate history of individual estates.

Nor is this the last word. It is clear there are abundant untapped areas of investigation in this whole field. It's a fascinating one, and as with other aspects of social history OpenStreetMap can play a useful part.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Sorry, as Google seem unable to filter obvious spam I now have to moderate comments. Please be patient.